How Ideas Find Structure

Innovation is often spoken about as if it were a single act — a breakthrough idea, a bold project, a moment of inspiration. Inside organisations, that framing quickly breaks down. People want innovation, but struggle to recognise where it begins, what it requires, or how it sustains itself over time.

What becomes clear, across disciplines and contexts, is that innovation is not an event. It is a system — a set of choices, structures, and rhythms that allow organisations to explore the future while remaining grounded in the present.

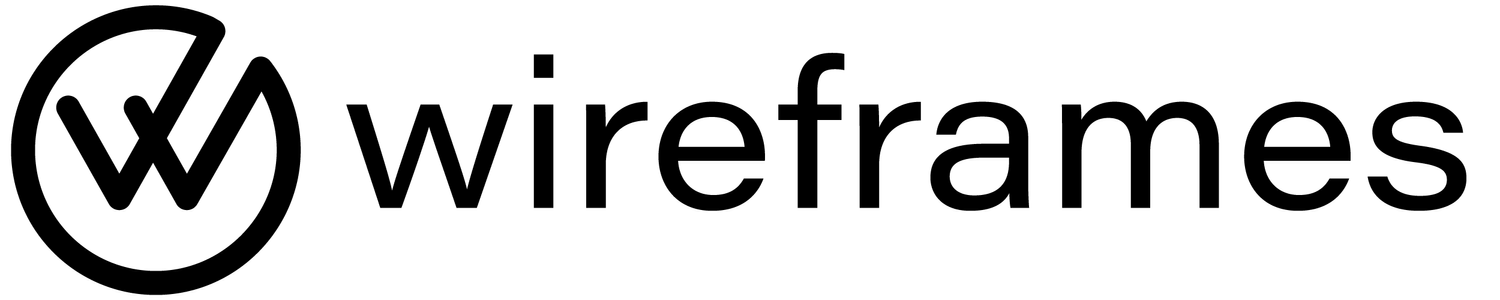

Three frameworks consistently surface as useful ways to understand this system. Each describes a different dimension of how ideas move from possibility to progress.

Where innovation lives

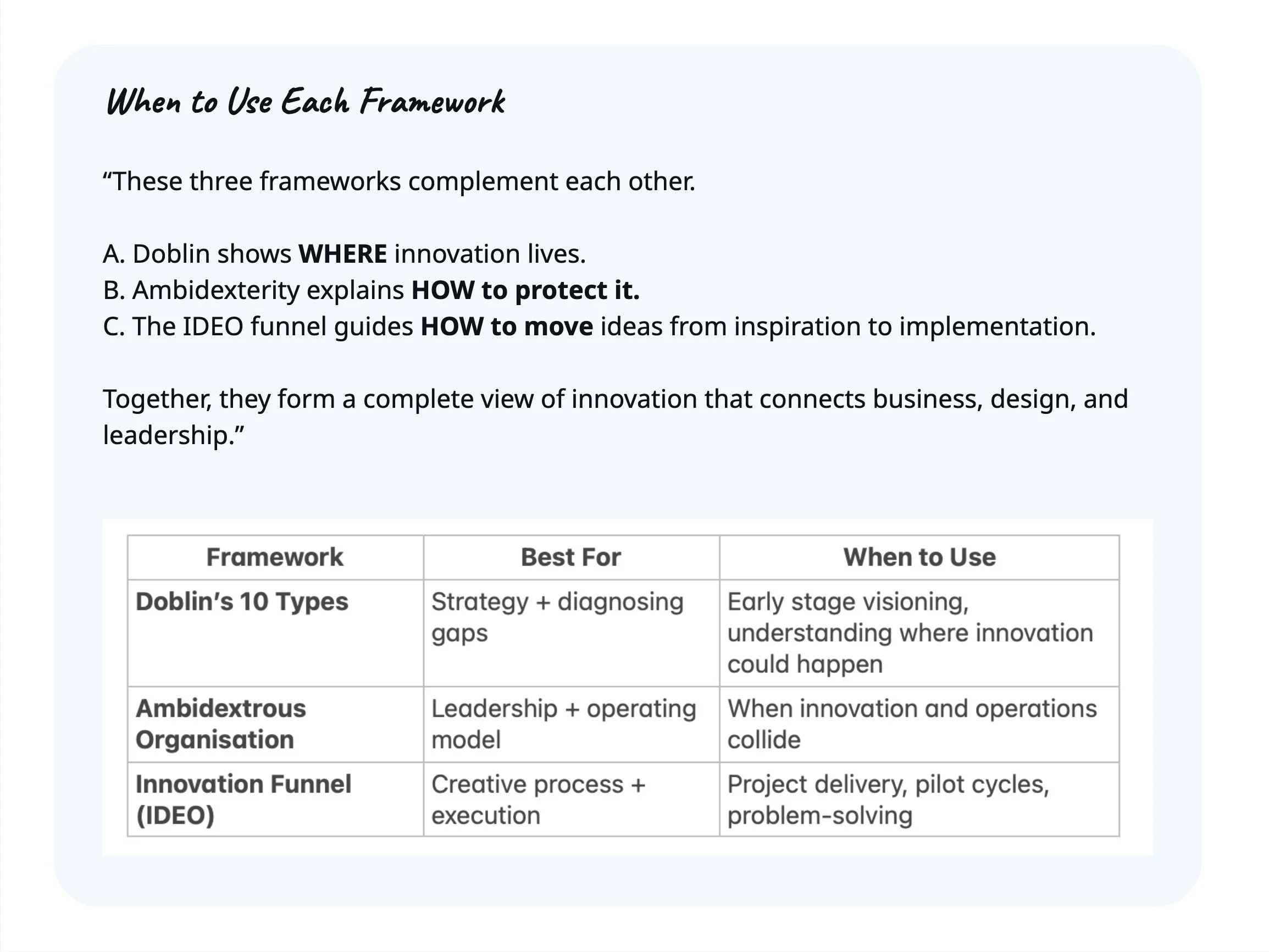

The first challenge is recognising where innovation can occur. Doblin’s 10 Types of Innovation expands the conversation beyond products and features, mapping innovation across business models, processes, partnerships, and experiences.

This perspective matters because it reveals opportunities that are often overlooked. Innovation may emerge from how value is created, how teams are organised, how work flows, or how people experience what is built. When teams feel stuck, this wider map often reveals that the problem is not a lack of ideas, but a narrow field of vision.

How organisations hold tension

Understanding where innovation can happen raises a second question: can the organisation support it?

The Ambidextrous Organisation describes a fundamental tension between two necessary forces. On one side, efficiency sustains the present — reliability, process, and optimisation. On the other, exploration creates the future — experimentation, uncertainty, and learning.

Both are essential. Problems arise when one overwhelms the other. When efficiency dominates, experimentation suffocates. When exploration runs unchecked, operations lose stability. Ambidexterity acknowledges that these forces must coexist, but not under the same rules. Innovation needs space, autonomy, and psychological safety. Operations need clarity, consistency, and trust.

Seeing this tension clearly explains why many initiatives stall: ideas disappear after workshops, pilots never scale, and organisations feel busy without becoming meaningfully different.

How ideas move forward

If structure defines the landscape and ambidexterity defines the tension, the Innovation Funnel explains movement.

Ideas rarely arrive fully formed. They emerge through observation, curiosity, and pattern-spotting. From there, possibilities are shaped, tested, combined, and challenged. Only later do they become pilots, systems, or products capable of surviving real constraints.

The discipline of the funnel protects teams from jumping too quickly to solutions. It keeps attention on learning before commitment, and on evidence before scale. Innovation, in this sense, is not linear progress but an ongoing dialogue between understanding and making.

A system, not a sequence

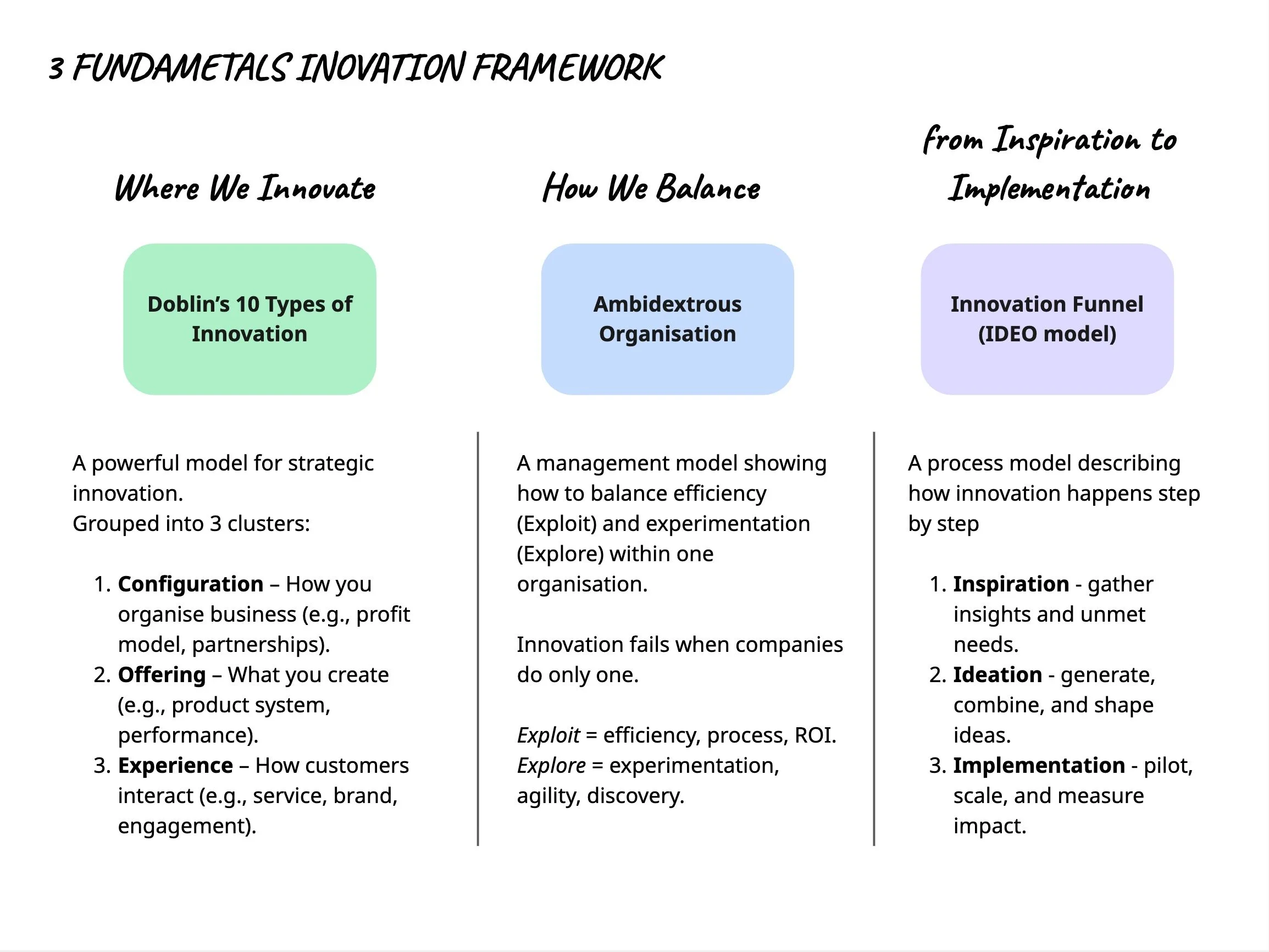

These frameworks are most powerful when they are not used in isolation.

Doblin helps reveal where innovation might emerge.

Ambidexterity helps design the conditions for it to survive.

The funnel provides a rhythm for turning insight into impact.

Together, they shift innovation from an abstract ambition into a shared system — one that blends clarity, courage, and craft.

Innovation becomes more achievable when we stop treating it as a destination and start understanding the structures that allow ideas to grow, adapt, and endure.