Designing a Job Search That Protects Attention

Problem

Job searching is not a lack-of-opportunity problem.

It is a signal, attention, and decision-quality problem.

Scanning hundreds of job descriptions creates noise, false hope, and cognitive fatigue.

The real challenge is deciding where not to spend energy, early and deliberately.

This experiment explores whether system design thinking can reduce noise, increase clarity, and protect motivation before emotions and sunk cost take over.

Framing the Experiment

I treated job search as a design problem, not an execution task.

Instead of asking:

Which job should I apply to?

I asked:

How might I design a system that consistently surfaces strong signals and avoids false positives?

Hypothesis :

Better filtering upstream → fewer decisions downstream → higher-quality applications.

The System (High-Level)

The system was designed in phases, each acting as a decision gate.

Two intentional choices:

Hard constraints (salary, location, contract type) were postponed

Early phases focused on signal and trajectory, not feasibility

This avoided killing opportunities before understanding their true nature.

Phase 0: Signal Collection

Input: ~100 job signals

Sources: LinkedIn alerts, emails, network pings

Action: Logged without judgment

No scoring. No filtering.

Only capturing the raw market signal.

Goal: Awareness without commitment.

Phase 1: First Scoring (Directional)

Each role was scored across five consistent dimensions:

Role Trajectory Fit

Does this move me toward meaningful execution leadership?Company Signal Strength

Brand, scale, ambition, and seriousness of innovation.Personal Energy Signal

Pull or resistance from title and company alone.Learning & Leverage Potential

Would success compound skills, network, or optionality?Credibility of Match

Can I imagine being hired without narrative gymnastics?

This was directional, not precise.

Tool note: ChatGPT was used for fast, consistent scoring once my context was clear.

The first week remained largely manual to validate logic and surface errors.

Phase 2 : Gatekeeper Check

At this stage, I asked only one question:

Is this role fundamentally about meaningful execution—or does it drift into work I’m no longer motivated by?

This eliminated roles that:

Were innovation-themed but execution-light

Were program management in name but sales-heavy in reality

Looked strategic but lacked ownership depth

This was a qualitative judgment, not a numerical one.

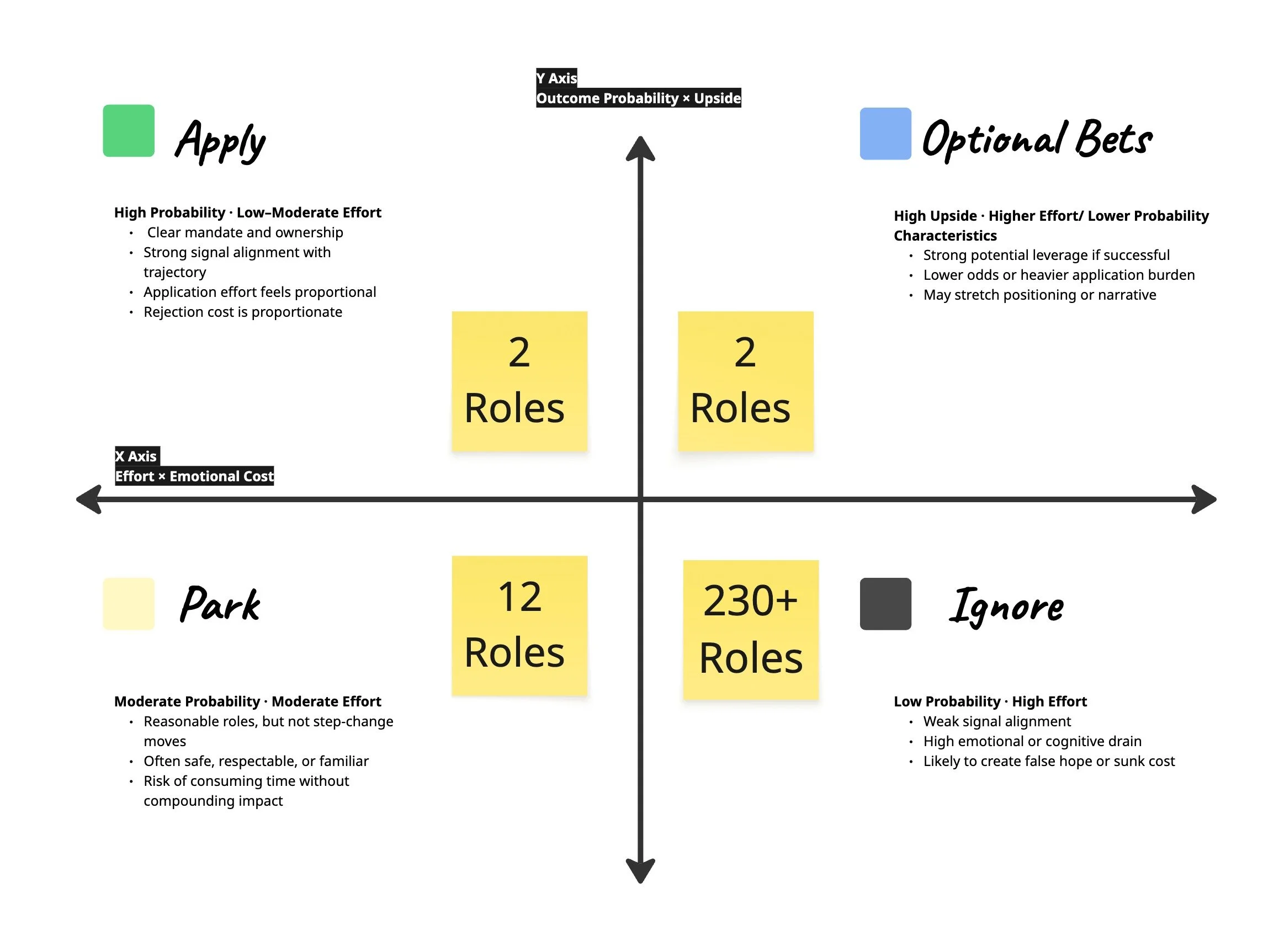

Phase 3: Probability × Effort Lens

Remaining roles were assessed through a pragmatic lens:

Probability of securing an interview

The effort required to apply well

Emotional cost of rejection

Upside if successful

This reframed applying as a portfolio decision, not an emotional one.

Phase 4: Job Description as Assumption Test

Only six roles made it to full Job description review.

Instead of skimming 100 JDs poorly, I read six deeply.

This surfaced a key insight:

Some roles that look right structurally fail on hidden filters (sales ownership, political complexity, unclear mandate).

After the JD review, only 2–3 roles remained worth applying to.

Monthly Indicator

~100 job signals collected

~20 progressed past early scoring

~6 reached full JD review

4 applications submitted

Cognitive load significantly reduced

Decision confidence increased

The system worked, not by finding a perfect role, but by protecting attention and energy.

Strategic Insight

The strongest signal was not about job titles.

It was about where leverage actually sits:

Not pure innovation

Not an abstract strategy

But meaningful execution with scope

This clarity didn’t come from thinking.

It came from designing and running the system.

Why Publish This?

This experiment is public by design.

Not because it is finished, but because:

Clarity follows action

Systems improve when externalised

This method may evolve into a product, tool, or framework

Wireframes exist as a record of thinking-through-making.

Even if no one reads this, the system has already paid for itself.

Closing Reflection

This system reduced noise, not uncertainty. And that is the point.

Good systems don’t eliminate doubt. They make doubt manageable and intentional.